From Denny's upcoming book "The Genesis Prophecies"

A Fruitful Bough

Jacob, the man who wrestled with God, knew he was about to die. He called his twelve sons to his bedside to impart a prophetic blessing over each one of them. His words, inspired by the Holy Spirit, paint a stunning prophetic picture of the future of Israel – her people, the first coming of the Messiah, and His return: “And Jacob called his sons and said, ‘Gather together, that I may tell you what shall befall you in the last days. Gather together and hear, you sons of Jacob, and listen to Israel your father.”[i] The phrase, “the last days” is an eschatological expression referring to the “time of the end” as revealed to all of God’s ancient Hebrew prophets. The words that Jacob spoke under the anointing of the Holy Spirit will mold the future of Israel until the second coming of the Messiah.

As his sons gathered at their father’s bedside, Jacob’s piercing gaze penetrated behind the veil of each of his sons’ lives to reveal the hidden things – things for which they would be commended or chastised.

Let’s focus our attention on the prophecy the patriarch spoke over one of his sons, Joseph: “Joseph is a fruitful bough, a fruitful bough by a well; his branches run over the wall.”[ii] With Jacob’s prophetic proclamation, the grape vine became one of the enduring symbols of Israel. A vine planted by a well of water, with branches growing over the wall and far outside the boundaries of the vineyard. Remember what the Lord had promised Joseph’s Great-Grandfather, Abraham: “In you all the families of the earth shall be blessed.”[iii] God’s sovereign plan was revealed. It is through Israel that He has blessed and will bless every family on earth. Okay, Denny, how does He do that? Great question. Paul, the apostle articulated seven glorious contributions that God has delivered to us all through Israel. These gifts have fashioned Western Civilization. Indeed, we often refer to our own Judeo-Christian heritage.

Throughout history and even today, the children of Israel are the guardians of the scrolls – the written word of God. Their scribes, like the one we encountered in an air conditioned, climate-controlled room on the top of Masada during a pastors’ tour of Israel, carefully copy by hand every letter and punctuation mark of Hebrew as they produce new Torah scrolls. You do know that we would not have any bible today if it had not been for the children of Israel. The sixty-six books in our bible – Old & New Testaments, were written in three languages by forty-four different Jewish authors on three continents over a 1,500-year period. What a miracle! What we know today as the New Testament was written in Greek, the common language of the 1st Century. Although none of the original manuscripts have been preserved, we do have ancient copies. The Codex Sinaiticus is one of four complete sets of the New Testament and Septuagint (the Torah translated into Greek) that exists today. They date back to the 4th Century and have been studied for centuries.

After Christianity became the official religion of the Roman Empire, in 382 AD, Pope Damasus I commissioned a priest by the name of Jerome to revise the Vetus Latina ("Old Latin") collection of biblical texts in Latin then in use by the Church. Jerome’s translation kept the bible out of the hands of the common people and the proprietary possession of the Roman Catholic priesthood for centuries. Thank God, that changed because of the efforts of John Wycliffe who translated the Latin Vulgate into English in the 14th Century, and then William Tyndale who translated the Hebrew and Greek texts into English in the 16th Century, at about the same time Martin Luther’s translation of the bible into German was first published.

Tyndale completed the printing of the New Testament in 1526. Tyndale’s translation was the first bible in English to take advantage of the printing press. On October 6, 1536, after fifteen months in prison, William Tyndale was strangled and burned at the stake for heresy. His last words were, “Lord, open the eyes of the King.” Tyndale’s prayer was answered when, because of the Hampton Court Conference of 1604, a new translation and compilation of approved books of the Bible was commissioned to resolve issues with different translations then being used. The Authorized King James Version, as it came to be known, was completed in 1611.

Once the bible was made accessible to the common people of England, a revival took place that produced the Separatists, also known as Puritans. They were mostly craftsmen – townspeople in Great Britain who after reading the bible for themselves had left the church of England to meet secretly in a town called Scrooby. King James I demanded that groups like them conform, or he would “Harry them out of the land!” In a series of daring and dangerous escapes, the Separatists fled religious persecution in England and settled for several years in Holland. But after their young people began to be lured away by the wickedness in Holland, their pastor, John Robinson, prayerfully led the church to consider re-locating the church in the New World of America.

As his sons gathered at their father’s bedside, Jacob’s piercing gaze penetrated behind the veil of each of his sons’ lives to reveal the hidden things – things for which they would be commended or chastised.

Let’s focus our attention on the prophecy the patriarch spoke over one of his sons, Joseph: “Joseph is a fruitful bough, a fruitful bough by a well; his branches run over the wall.”[ii] With Jacob’s prophetic proclamation, the grape vine became one of the enduring symbols of Israel. A vine planted by a well of water, with branches growing over the wall and far outside the boundaries of the vineyard. Remember what the Lord had promised Joseph’s Great-Grandfather, Abraham: “In you all the families of the earth shall be blessed.”[iii] God’s sovereign plan was revealed. It is through Israel that He has blessed and will bless every family on earth. Okay, Denny, how does He do that? Great question. Paul, the apostle articulated seven glorious contributions that God has delivered to us all through Israel. These gifts have fashioned Western Civilization. Indeed, we often refer to our own Judeo-Christian heritage.

Throughout history and even today, the children of Israel are the guardians of the scrolls – the written word of God. Their scribes, like the one we encountered in an air conditioned, climate-controlled room on the top of Masada during a pastors’ tour of Israel, carefully copy by hand every letter and punctuation mark of Hebrew as they produce new Torah scrolls. You do know that we would not have any bible today if it had not been for the children of Israel. The sixty-six books in our bible – Old & New Testaments, were written in three languages by forty-four different Jewish authors on three continents over a 1,500-year period. What a miracle! What we know today as the New Testament was written in Greek, the common language of the 1st Century. Although none of the original manuscripts have been preserved, we do have ancient copies. The Codex Sinaiticus is one of four complete sets of the New Testament and Septuagint (the Torah translated into Greek) that exists today. They date back to the 4th Century and have been studied for centuries.

After Christianity became the official religion of the Roman Empire, in 382 AD, Pope Damasus I commissioned a priest by the name of Jerome to revise the Vetus Latina ("Old Latin") collection of biblical texts in Latin then in use by the Church. Jerome’s translation kept the bible out of the hands of the common people and the proprietary possession of the Roman Catholic priesthood for centuries. Thank God, that changed because of the efforts of John Wycliffe who translated the Latin Vulgate into English in the 14th Century, and then William Tyndale who translated the Hebrew and Greek texts into English in the 16th Century, at about the same time Martin Luther’s translation of the bible into German was first published.

Tyndale completed the printing of the New Testament in 1526. Tyndale’s translation was the first bible in English to take advantage of the printing press. On October 6, 1536, after fifteen months in prison, William Tyndale was strangled and burned at the stake for heresy. His last words were, “Lord, open the eyes of the King.” Tyndale’s prayer was answered when, because of the Hampton Court Conference of 1604, a new translation and compilation of approved books of the Bible was commissioned to resolve issues with different translations then being used. The Authorized King James Version, as it came to be known, was completed in 1611.

Once the bible was made accessible to the common people of England, a revival took place that produced the Separatists, also known as Puritans. They were mostly craftsmen – townspeople in Great Britain who after reading the bible for themselves had left the church of England to meet secretly in a town called Scrooby. King James I demanded that groups like them conform, or he would “Harry them out of the land!” In a series of daring and dangerous escapes, the Separatists fled religious persecution in England and settled for several years in Holland. But after their young people began to be lured away by the wickedness in Holland, their pastor, John Robinson, prayerfully led the church to consider re-locating the church in the New World of America.

This painting, commissioned by the US Congress, hangs in the rotunda of the US Capitol Building in Washington, DC, forever commemorating the departure of the Pilgrims from Holland in search for freedom in the New World.

The painting depicts the Pilgrims on the deck of the ship Speedwell on July 22, 1620, before they departed from Delfshaven, Holland, for North America, where they sought religious freedom. The group appears solemn and contemplative of what they are about to undertake as they pray for divine protection through their voyage. The words “God with us” appear on the sail in the upper left corner. The figures at the center of the composition are William Brewster, holding the Bible; Governor Carver, kneeling with head bowed and hat in hand; and pastor John Robinson, with extended arms, looking Heavenward.

They first sailed to Southampton, England, to join the Mayflower, which was also booked for the voyage to America. After leaks forced Speedwell to make additional stops in Dartmouth and then Plymouth, the Pilgrims realized that they would have to make their voyage on the Mayflower alone. The prayed and decided who would continue and who would stay behind. Pastor John Robinson was one of those left behind. On September 6, 1620, the Pilgrims were finally on their way to the New World. Initially the trip went smoothly, but under way they were met with fierce winds and storms. One of these caused a main beam to crack, and although they were more than half the way to their destination, the possibility of turning back was considered. Using a "great iron screw” brought along by the colonists, they repaired the ship sufficiently to continue. One passenger, John Howland, was washed overboard in the storm but caught a top sail halyard trailing in the water and was pulled back on board.

Land was sighted on November 9, 1620. They had intended to join the Virginia Bay Colony, but due to weather and rough seas they missed their intended destination by about 150 miles. The passengers who had endured miserable conditions for about sixty-five days were led by William Brewster in Psalm 100 as a prayer of thanksgiving: “Make a joyful shout to the Lord, all you lands! Serve the Lord with gladness; come before His presence with singing. Know that the Lord, He is God; it is He who has made us, and not we ourselves; we are His people and the sheep of His pasture. Enter into His gates with thanksgiving, and into His courts with praise. Be thankful to Him, and bless His name. For the Lord is good; His mercy is everlasting, and His truth endures to all generations.”[i] Before they disembarked, they huddled beneath the deck and drafted a self-governing document they called the Mayflower Compact that begins: “In the Name of God” and gave this reason for their coming:

“For the Glory of God and the Advancement of the Christian Faith.”

William Bradford described the Pilgrim’s thankfulness when they finally set their feet on the shores of North America: “Being thus arived in a good harbor and brought safe to land, they fell upon their knees & blessed ye God of heaven who had brought them over ye vast & furious ocean, and delivered them from all ye periles & miseries therof, againe to set their feete on ye firme and stable earth, their proper elemente… What could now sustain them but the Spirit of God and His grace?”[ii]

Thirty years after landing in America, at the age of sixty, William Bradford, then the Governor of the Plymouth Colony, decided to learn Hebrew: “Though I have grown aged, yet I have a longing desire to see with my own eyes, something of that most ancient language, and Holy Tongue the Law and the Oracles of God were writ…and which God spoke to the holy Patriarchs of old time. My aim and desire is to look on the words and phrases of the Holy Text; and to discern somewhat of the same for my own content.”[iii] As the Pilgrims firmly planted their feet in America, Hebrew and the bible became the stalwart of their founding of various educational institutions.

With some 17,000 separatists migrating to New England by 1636, Harvard was founded in anticipation of the need for training clergy for the new commonwealth, a "church in the wilderness". Harvard was established in 1636 by vote of the Great and General Court of the Massachusetts Bay Colony. Engraved on two plaques on the pillars of the Johnston Gate, beneath a wrought iron cross, are these words:

After God had carried us safe to New-England, and we had builded our houses, provided necessaries for our livelihood, rear’d convenient places for Gods worship, and setled the Civill Government: One of the next things we longed for, and looked after was to advance Learning and perpetuate it to Posterity; dreading to leave an illiterate Ministery to the Churches, when our present Ministers shall lie in the Dust. And as we were thinking and consulting how to effect this great work, it pleased God to stir up the heart of one Mr. Harvard (a godly gentleman and a lover of learning; then living amongst us) to give one-half of his estate (it being in all about £1,700) towards the erecting of a College, and all his library.

The painting depicts the Pilgrims on the deck of the ship Speedwell on July 22, 1620, before they departed from Delfshaven, Holland, for North America, where they sought religious freedom. The group appears solemn and contemplative of what they are about to undertake as they pray for divine protection through their voyage. The words “God with us” appear on the sail in the upper left corner. The figures at the center of the composition are William Brewster, holding the Bible; Governor Carver, kneeling with head bowed and hat in hand; and pastor John Robinson, with extended arms, looking Heavenward.

They first sailed to Southampton, England, to join the Mayflower, which was also booked for the voyage to America. After leaks forced Speedwell to make additional stops in Dartmouth and then Plymouth, the Pilgrims realized that they would have to make their voyage on the Mayflower alone. The prayed and decided who would continue and who would stay behind. Pastor John Robinson was one of those left behind. On September 6, 1620, the Pilgrims were finally on their way to the New World. Initially the trip went smoothly, but under way they were met with fierce winds and storms. One of these caused a main beam to crack, and although they were more than half the way to their destination, the possibility of turning back was considered. Using a "great iron screw” brought along by the colonists, they repaired the ship sufficiently to continue. One passenger, John Howland, was washed overboard in the storm but caught a top sail halyard trailing in the water and was pulled back on board.

Land was sighted on November 9, 1620. They had intended to join the Virginia Bay Colony, but due to weather and rough seas they missed their intended destination by about 150 miles. The passengers who had endured miserable conditions for about sixty-five days were led by William Brewster in Psalm 100 as a prayer of thanksgiving: “Make a joyful shout to the Lord, all you lands! Serve the Lord with gladness; come before His presence with singing. Know that the Lord, He is God; it is He who has made us, and not we ourselves; we are His people and the sheep of His pasture. Enter into His gates with thanksgiving, and into His courts with praise. Be thankful to Him, and bless His name. For the Lord is good; His mercy is everlasting, and His truth endures to all generations.”[i] Before they disembarked, they huddled beneath the deck and drafted a self-governing document they called the Mayflower Compact that begins: “In the Name of God” and gave this reason for their coming:

“For the Glory of God and the Advancement of the Christian Faith.”

William Bradford described the Pilgrim’s thankfulness when they finally set their feet on the shores of North America: “Being thus arived in a good harbor and brought safe to land, they fell upon their knees & blessed ye God of heaven who had brought them over ye vast & furious ocean, and delivered them from all ye periles & miseries therof, againe to set their feete on ye firme and stable earth, their proper elemente… What could now sustain them but the Spirit of God and His grace?”[ii]

Thirty years after landing in America, at the age of sixty, William Bradford, then the Governor of the Plymouth Colony, decided to learn Hebrew: “Though I have grown aged, yet I have a longing desire to see with my own eyes, something of that most ancient language, and Holy Tongue the Law and the Oracles of God were writ…and which God spoke to the holy Patriarchs of old time. My aim and desire is to look on the words and phrases of the Holy Text; and to discern somewhat of the same for my own content.”[iii] As the Pilgrims firmly planted their feet in America, Hebrew and the bible became the stalwart of their founding of various educational institutions.

With some 17,000 separatists migrating to New England by 1636, Harvard was founded in anticipation of the need for training clergy for the new commonwealth, a "church in the wilderness". Harvard was established in 1636 by vote of the Great and General Court of the Massachusetts Bay Colony. Engraved on two plaques on the pillars of the Johnston Gate, beneath a wrought iron cross, are these words:

After God had carried us safe to New-England, and we had builded our houses, provided necessaries for our livelihood, rear’d convenient places for Gods worship, and setled the Civill Government: One of the next things we longed for, and looked after was to advance Learning and perpetuate it to Posterity; dreading to leave an illiterate Ministery to the Churches, when our present Ministers shall lie in the Dust. And as we were thinking and consulting how to effect this great work, it pleased God to stir up the heart of one Mr. Harvard (a godly gentleman and a lover of learning; then living amongst us) to give one-half of his estate (it being in all about £1,700) towards the erecting of a College, and all his library.

Harvard was dedicated to the truth, as graphically depicted in this sketch, which became the seal of Harvard College.

The original curriculum of the College included more Hebrew studies than any other single subject. Hebrew and the study of the Old Testament were essential for every student. The results would prove to guide the formation of the new nation.

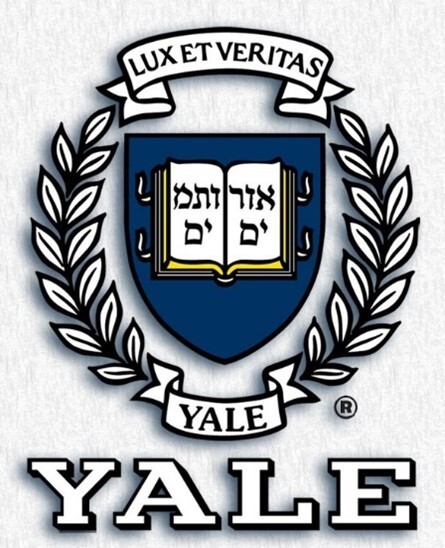

At Yale University, beneath the banner containing the Latin phrase, Lux Et Veritas

(love of the truth), the Yale seal shows an open book with the Hebrew Urim V’Timum

(lights and perfections) - a part of the breastplate worn by the Jewish High Priest.

(love of the truth), the Yale seal shows an open book with the Hebrew Urim V’Timum

(lights and perfections) - a part of the breastplate worn by the Jewish High Priest.

At Dartmouth College in New Hampshire, the seal has the Hebrew words meaning “God Almighty” inside a triangle at the top center with rays of glory emanating from the triangle.

At Kings College in New York City, now known as Columbia University, the seal has the Hebrew name for God at the top center with rays of glory emanating from the Name.

Many of our founding fathers were students at these universities. Thomas Jefferson attended William and Mary, James Madison attended Princeton, Alexander Hamilton attended Kings College. Thus, we can be certain that many of these political leaders were not only students of the scriptures, but also had studied Hebrew.

The early American settlers turned to the bible, and specifically to the Hebrew scriptures, what we call the Old Testament, to provide wisdom in the building of their civil government. According to the New Haven Colony Charter adopted in 1644:

“The judicial laws of God, as they were delivered by Moses… are to be a rule to all the courts in this jurisdiction.” It was William Penn’s belief that the law and civil magistrates should protect and preserve liberty, not licentiousness, immorality, and injustice. In 1682, he wrote in the fundamental Constitution of Pennsylvania:

“Whereas the glory of Almighty God and the good of mankind is the reason and end of government, and therefore, government itself is a venerable ordinance of God there shall be established laws as shall best preserve true Christian and civil authority, in opposition to all un-Christian, licentious and unjust practices.”[i]

In that same document he went on: “The origin and descent of all human power is from God…first, to terrify evil doers; secondly, to cherish those who do well.”[i] “Government seems to me to be a part of religion itself – a thing sacred in its institutions and ends.”[ii] “Government, like clocks, go from the motion men give them; and as governments are made and moved by men, so by them they are ruined too.”[iii]

Meanwhile, back in England, the First English Civil War erupted in 1642. Over time, the monarchy in England was essentially dethroned, and the Commonwealth of England was the result of the efforts of Oliver Cromwell. Emboldened by their successes on the battlefield, the Church of England came under the protectorate of Oliver Cromwell. And the Puritans, taking the bible literally, and studying it for themselves, began to realize that indeed, God had not cast away the people of Israel, the descendants of Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob.

On January 5, 1648, the following petition was addressed, “To the Right Honorable Thomas Lord Fairfax, and the Honorable Council of Warre, convened for God’s Glory, Israel’s Freedom, Peace and Safety:” The petition called for an official change of heart in Great Britain toward the Jews:

With and amongst some of the Izraell race called Jewes, and growing sensible of their heavy out-cryes and clamours against the intolerable cruelty of this our English Nation, exercised against them by that ... inhumane ... massacre ... and their banishment ever since, that by discourse with them, and serious perusal of the Prophets, both they and we find, that the time of her call draweth nigh ...and that this Nation of England, with the inhabitants of the Netherlands, shall be the first and readiest to transport Izraells sons and daughters in their ships to the land promised to their forefathers, Abraham, Isaac and Jacob, for an everlasting inheritance.[iv]

Many of the believers in England became enamored with the Old Testament and began using the ancient Hebrew names like “Isaac” when naming their children. In addition to being a brilliant scientist, Sir Isaac Newton was also a believer who diligently studied his bible and predicted: “About the time of the End, a body of men will be raised up who will turn their attention to the prophecies and insist on their literal interpretation in the midst of much clamor and opposition.”

In her benchmark book, Bible and Sword, England and Palestine from the Bronze Age to Balfour, Barbara Tuchman wrote: “With the translation of the Bible into English and its adoption as the highest authority for an autonomous English Church, the history, traditions, and moral law of the Hebrew nation became part of the English culture; became for a period of three centuries the most powerful single influence on that culture. It linked, to repeat Matthew Arnold’s phrase, ‘the genius and history of us English, and our American descendants across the Atlantic, to the genius and history of the Hebrew people.’”[i] Indeed, the fruitful bough which had been planted by a well was growing over the wall. The impact that Judaism had on life in America is unmistakable. We continue to be the longest on-going Constitutional Republic in the history of the world. Blessings such as these are not by chance or accidental.

They are blessings of God.

Where did our founding fathers get their ideas for creating this Republic? In his thorough research for his book, The Origins of American Constitutionalism, author Donald Lutz examined 3,154 quotes from sources in the writings of our founders. He discovered that famous French lawyer of the Enlightenment, Montesquieu, was the source of 8.3% of the quotes used in the writings of our founders. He discovered that famous British jurist, Sir William Blackstone, was the source of 7.9% of the quotes used in the writings of our founders. He discovered that famous British philosopher and physician, Sir William Blackstone, was the source of just 2.4% of the quotes used in the writings of our founders. He also discovered that the holy bible was the source of 34% of the quotes used in the writings of our founders. What should be interesting for us to consider is that in our founders’ writings of official government documents, there is not one New Testament passage quoted! The Old Testament was the source of inspiration for the founding of our civil government, especially the Book of Deuteronomy.

Prior to the American Revolution, the only English Bibles in the colonies were imported either from Europe or England. Publication of the Bible was regulated by the British government and required a special license. Robert Aitken’s Bible was the first known English-language Bible to be printed in America, and the only Bible to receive Congressional approval. Aitken’s Bible, sometimes referred to as “The Bible of the Revolution,” is one of the rarest books in the world, with few copies still in existence today.

During the Second Continental Congress, a committee was assigned the task of creating a great seal for the United States of America. The committee members were Benjamin Franklin, John Adams, and Thomas Jefferson. This is the artist’s rendering of their concept for the Great Seal of the United States –

The early American settlers turned to the bible, and specifically to the Hebrew scriptures, what we call the Old Testament, to provide wisdom in the building of their civil government. According to the New Haven Colony Charter adopted in 1644:

“The judicial laws of God, as they were delivered by Moses… are to be a rule to all the courts in this jurisdiction.” It was William Penn’s belief that the law and civil magistrates should protect and preserve liberty, not licentiousness, immorality, and injustice. In 1682, he wrote in the fundamental Constitution of Pennsylvania:

“Whereas the glory of Almighty God and the good of mankind is the reason and end of government, and therefore, government itself is a venerable ordinance of God there shall be established laws as shall best preserve true Christian and civil authority, in opposition to all un-Christian, licentious and unjust practices.”[i]

In that same document he went on: “The origin and descent of all human power is from God…first, to terrify evil doers; secondly, to cherish those who do well.”[i] “Government seems to me to be a part of religion itself – a thing sacred in its institutions and ends.”[ii] “Government, like clocks, go from the motion men give them; and as governments are made and moved by men, so by them they are ruined too.”[iii]

Meanwhile, back in England, the First English Civil War erupted in 1642. Over time, the monarchy in England was essentially dethroned, and the Commonwealth of England was the result of the efforts of Oliver Cromwell. Emboldened by their successes on the battlefield, the Church of England came under the protectorate of Oliver Cromwell. And the Puritans, taking the bible literally, and studying it for themselves, began to realize that indeed, God had not cast away the people of Israel, the descendants of Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob.

On January 5, 1648, the following petition was addressed, “To the Right Honorable Thomas Lord Fairfax, and the Honorable Council of Warre, convened for God’s Glory, Israel’s Freedom, Peace and Safety:” The petition called for an official change of heart in Great Britain toward the Jews:

With and amongst some of the Izraell race called Jewes, and growing sensible of their heavy out-cryes and clamours against the intolerable cruelty of this our English Nation, exercised against them by that ... inhumane ... massacre ... and their banishment ever since, that by discourse with them, and serious perusal of the Prophets, both they and we find, that the time of her call draweth nigh ...and that this Nation of England, with the inhabitants of the Netherlands, shall be the first and readiest to transport Izraells sons and daughters in their ships to the land promised to their forefathers, Abraham, Isaac and Jacob, for an everlasting inheritance.[iv]

Many of the believers in England became enamored with the Old Testament and began using the ancient Hebrew names like “Isaac” when naming their children. In addition to being a brilliant scientist, Sir Isaac Newton was also a believer who diligently studied his bible and predicted: “About the time of the End, a body of men will be raised up who will turn their attention to the prophecies and insist on their literal interpretation in the midst of much clamor and opposition.”

In her benchmark book, Bible and Sword, England and Palestine from the Bronze Age to Balfour, Barbara Tuchman wrote: “With the translation of the Bible into English and its adoption as the highest authority for an autonomous English Church, the history, traditions, and moral law of the Hebrew nation became part of the English culture; became for a period of three centuries the most powerful single influence on that culture. It linked, to repeat Matthew Arnold’s phrase, ‘the genius and history of us English, and our American descendants across the Atlantic, to the genius and history of the Hebrew people.’”[i] Indeed, the fruitful bough which had been planted by a well was growing over the wall. The impact that Judaism had on life in America is unmistakable. We continue to be the longest on-going Constitutional Republic in the history of the world. Blessings such as these are not by chance or accidental.

They are blessings of God.

Where did our founding fathers get their ideas for creating this Republic? In his thorough research for his book, The Origins of American Constitutionalism, author Donald Lutz examined 3,154 quotes from sources in the writings of our founders. He discovered that famous French lawyer of the Enlightenment, Montesquieu, was the source of 8.3% of the quotes used in the writings of our founders. He discovered that famous British jurist, Sir William Blackstone, was the source of 7.9% of the quotes used in the writings of our founders. He discovered that famous British philosopher and physician, Sir William Blackstone, was the source of just 2.4% of the quotes used in the writings of our founders. He also discovered that the holy bible was the source of 34% of the quotes used in the writings of our founders. What should be interesting for us to consider is that in our founders’ writings of official government documents, there is not one New Testament passage quoted! The Old Testament was the source of inspiration for the founding of our civil government, especially the Book of Deuteronomy.

Prior to the American Revolution, the only English Bibles in the colonies were imported either from Europe or England. Publication of the Bible was regulated by the British government and required a special license. Robert Aitken’s Bible was the first known English-language Bible to be printed in America, and the only Bible to receive Congressional approval. Aitken’s Bible, sometimes referred to as “The Bible of the Revolution,” is one of the rarest books in the world, with few copies still in existence today.

During the Second Continental Congress, a committee was assigned the task of creating a great seal for the United States of America. The committee members were Benjamin Franklin, John Adams, and Thomas Jefferson. This is the artist’s rendering of their concept for the Great Seal of the United States –

"Moses standing on the Shore, and extending his Hand over the Sea, thereby causing the same to overwhelm Pharaoh who is sitting in an open Chariot, a Crown on his Head and a Sword in his Hand. Rays from a Pillar of Fire in the Clouds reaching to Moses, to express that he acts by Command of the Deity.”

Their chosen motto: “Rebellion to Tyrants is Obedience to God.”

On July 2, 1776, the Second Continental Congress voted to approve a complete separation from Great Britain. Two days afterwards – July 4th – the early draft of the Declaration of Independence was signed, albeit by only two individuals at that time: John Hancock, President of Congress, and Charles Thompson, Secretary of Congress. Four days later, on July 8, church bells rang to call the citizens of Philadelphia to gather in front of the State House. At noon, Col. John Nixon took that document and read it aloud from the steps of the State House, proclaiming it to the city of Philadelphia, after which the Liberty Bell was rung. The inscription around the top of that bell, from Leviticus 25:10, was most appropriate for the occasion: “Proclaim liberty throughout the land and to all the inhabitants thereof.” What is more interesting to me is the text from which the inscription was taken. Speaker of the Pennsylvania Assembly Isaac Norris chose this inscription for the State House bell in 1751, to commemorate the fiftieth anniversary of William Penn's 1701 Charter of Privileges which granted religious liberties and political self-government to the people of Pennsylvania: “And you shall consecrate the fiftieth year, and proclaim liberty throughout all the land to all its inhabitants. It shall be a Jubilee for you; and each of you shall return to his possession, and each of you shall return to his family.”[i]

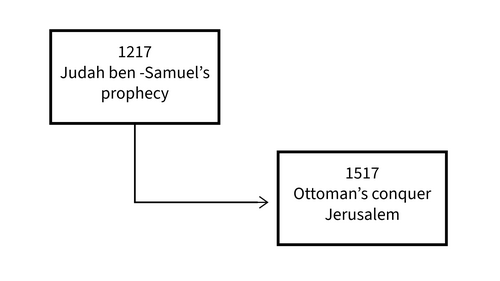

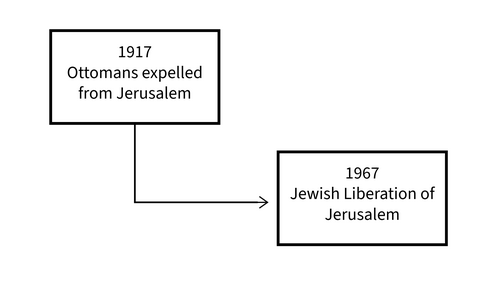

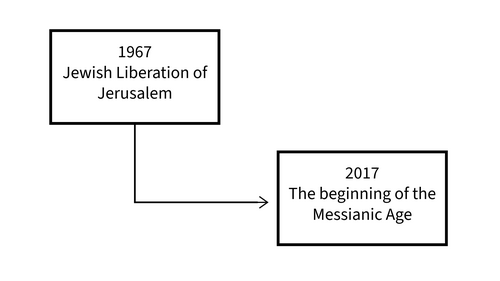

Let me introduce you to Judah ben Samuel of Regensburg, Germany. This 12th Century Jewish Rabbi was also known as HeHasid, or “the Pious” in Hebrew. He believed that God’s eternal plan for man could be traced by the Jubilee. Before his death in 1217, he wrote that in six Jubilees the Ottomans would conquer Jerusalem, and that “When the Ottomans (Turks) – who were already a power to be reckoned with on the Bosporus in the time of Judah Ben Samuel – conquer Jerusalem they will rule over Jerusalem for eight jubilees. Afterwards Jerusalem will become no-man’s land for one jubilee, and then in the tenth jubilee it will once again come back into the possession of the Jewish nation – which would signify the beginning of the Messianic end time.”[ii] 300 years later, in 1517, the Ottoman’s defeated the Mamluk’s who had occupied Jerusalem since 1250.

Their chosen motto: “Rebellion to Tyrants is Obedience to God.”

On July 2, 1776, the Second Continental Congress voted to approve a complete separation from Great Britain. Two days afterwards – July 4th – the early draft of the Declaration of Independence was signed, albeit by only two individuals at that time: John Hancock, President of Congress, and Charles Thompson, Secretary of Congress. Four days later, on July 8, church bells rang to call the citizens of Philadelphia to gather in front of the State House. At noon, Col. John Nixon took that document and read it aloud from the steps of the State House, proclaiming it to the city of Philadelphia, after which the Liberty Bell was rung. The inscription around the top of that bell, from Leviticus 25:10, was most appropriate for the occasion: “Proclaim liberty throughout the land and to all the inhabitants thereof.” What is more interesting to me is the text from which the inscription was taken. Speaker of the Pennsylvania Assembly Isaac Norris chose this inscription for the State House bell in 1751, to commemorate the fiftieth anniversary of William Penn's 1701 Charter of Privileges which granted religious liberties and political self-government to the people of Pennsylvania: “And you shall consecrate the fiftieth year, and proclaim liberty throughout all the land to all its inhabitants. It shall be a Jubilee for you; and each of you shall return to his possession, and each of you shall return to his family.”[i]

Let me introduce you to Judah ben Samuel of Regensburg, Germany. This 12th Century Jewish Rabbi was also known as HeHasid, or “the Pious” in Hebrew. He believed that God’s eternal plan for man could be traced by the Jubilee. Before his death in 1217, he wrote that in six Jubilees the Ottomans would conquer Jerusalem, and that “When the Ottomans (Turks) – who were already a power to be reckoned with on the Bosporus in the time of Judah Ben Samuel – conquer Jerusalem they will rule over Jerusalem for eight jubilees. Afterwards Jerusalem will become no-man’s land for one jubilee, and then in the tenth jubilee it will once again come back into the possession of the Jewish nation – which would signify the beginning of the Messianic end time.”[ii] 300 years later, in 1517, the Ottoman’s defeated the Mamluk’s who had occupied Jerusalem since 1250.

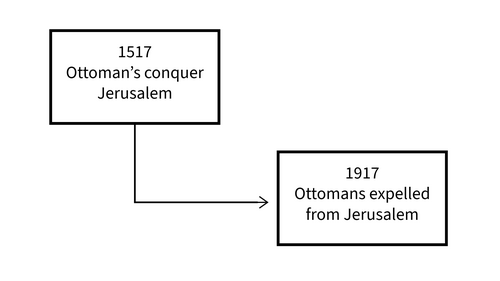

He prophesied that the Ottoman’s would occupy Jerusalem for eight Jubilee’s, and that is exactly what happened. In 1917, the British General Allenby defeated the Ottoman occupiers and expelled them from Jerusalem.

Immediately afterward, the League of Nations conferred the Mandate for the Holy Land and Jerusalem to the British. Thus, from 1917, under international law, Jerusalem was no-man’s land, just as the prophecy of Judah ben Samuel had indicated.

Then, when Israel captured Jerusalem in the Six Day War of 1967, exactly one jubilee (50 years) after 1917, Jerusalem reverted to Jewish-Israeli ownership once again.

Then, when Israel captured Jerusalem in the Six Day War of 1967, exactly one jubilee (50 years) after 1917, Jerusalem reverted to Jewish-Israeli ownership once again.

At the end of the tenth Jubilee, Judah ben-Samuel wrote that the Messianic Age would begin. So, that would mean 2017 ushered the beginning of the Messianic Age according to this pious Rabbi.

Each year, millions of visitors to our nation’s capital visit our National Archives and stand in long lines to gain access to the rotunda where the original Declaration of Independence and Constitution of the United States of America are on guarded display. The original Constitution is written on four large sheets of parchment and contains a preamble, seven Articles, a closing endorsement, and the signatures of thirty-nine of the original fifty-five delegates. Those thirty-nine men ratified it and signed it on September 17, 1787 – more than eleven years after the signing of the Declaration of Independence. The Constitution decrees the balance of powers between the three branches of our Federal Government. Where did our founders get that idea? Directly from the word of God as they read the prophecies of Isaiah. “For the Lord is our Judge, the Lord is our Lawgiver, the Lord is our King; He will save us.”[i] “The Lord is our Judge” provided the basis for our Judicial System – Article III of our Constitution. “The Lord is our Lawgiver” provided the basis for our Legislative System – Article I of our Constitution. “The Lord is our King” provided the basis for our Executive Branch – Article II of our Constitution. “He will save us” provided the basis for our National Motto: In God We Trust - a phrase that is emblazoned over the entrance to the Visitor’s Center in the US Capitol Building and on our paper money and our coins. George Washington, who presided over the Constitutional Convention that began on May 25, 1787, would later say on April 30, 1789, during his first inaugural address: “The propitious smiles of heaven can never be expected on a nation that disregards the eternal rules of order and right which heaven itself has ordained.”

One of our first President’s priorities was the final ratification of the US Constitution by all the States. In the fall of 1789, he visited New England, but intentionally bypassed Rhode Island who had refused to call a state convention to ratify the Constitution at that time. He decided to make a public trip to the state only after May 1790, when Rhode Island ratified the Constitution. On the morning of August 17, 1790, George Washington arrived in Newport, Rhode Island. He was accompanied by Secretary of State Thomas Jefferson, Governor George Clinton of New York, U.S. Supreme Court Justice John Blair of Virginia, and U.S. Congressman William Loughton Smith of South Carolina. Washington and his group were greeted by Newport’s leading citizens and representatives from the many religious denominations present in the city. Politicians, businessmen, and clergy read letters of welcome to the President. Among them was Moses Seixas, one of the officials of Yeshuat Israel, the first Jewish congregation in Newport. The address read by Seixas was an elegant expression of the Jewish community’s delight in Washington as leader and in a democratic government.

In gratitude for the endorsement of the Jewish congregation, Washington sent a letter addressed “To the Hebrew congregation in Newport, Rhode Island.” He wrote: “May the children of the stock of Abraham who dwell in this land continue to merit and enjoy the good will of the other inhabitants while every one shall sit in safety under his own vine and fig tree and there shall be none to make him afraid. May the father of all mercies scatter light, and not darkness, upon our paths, and make us all in our several vocations useful here, and in His own due time and way everlastingly happy.”[ii]

During the Revolutionary War, George Washington had been supported financially by a Jewish financier, Haym Salomon, whose bronze sculpture stands at the left hand of Washington at the Heald Square Monument in Chicago, Illinois. It depicts General George Washington, and the two principal financers of the American Revolution, Robert Morris and Haym Salomon. In 1925, President Calvin Coolidge eloquently recounted Haym Salomon’s contributions and personal sacrifices for the cause of liberty: “Haym Salomon, Polish Jew financier of the Revolution. Born in Poland, he was made prisoner by the British forces in New York, and when he escaped set up in business in Philadelphia. He negotiated for Robert Morris all the loans raised in France and Holland, pledged his personal faith and fortune for enormous amounts, and personally advanced large sums to such men as James Madison, Thomas Jefferson, and many other patriot leaders who testified that without his aid they could not have carried on in the cause.”[iii] In 1975, a U.S. ten-cent postage stamp honored Haym Solomon, with printing on the back: “Financial hero-businessman and broker Haym Solomon was responsible for raising most of the money needed to finance the American Revolution and later saved the new nation from collapse.”

One of our first President’s priorities was the final ratification of the US Constitution by all the States. In the fall of 1789, he visited New England, but intentionally bypassed Rhode Island who had refused to call a state convention to ratify the Constitution at that time. He decided to make a public trip to the state only after May 1790, when Rhode Island ratified the Constitution. On the morning of August 17, 1790, George Washington arrived in Newport, Rhode Island. He was accompanied by Secretary of State Thomas Jefferson, Governor George Clinton of New York, U.S. Supreme Court Justice John Blair of Virginia, and U.S. Congressman William Loughton Smith of South Carolina. Washington and his group were greeted by Newport’s leading citizens and representatives from the many religious denominations present in the city. Politicians, businessmen, and clergy read letters of welcome to the President. Among them was Moses Seixas, one of the officials of Yeshuat Israel, the first Jewish congregation in Newport. The address read by Seixas was an elegant expression of the Jewish community’s delight in Washington as leader and in a democratic government.

In gratitude for the endorsement of the Jewish congregation, Washington sent a letter addressed “To the Hebrew congregation in Newport, Rhode Island.” He wrote: “May the children of the stock of Abraham who dwell in this land continue to merit and enjoy the good will of the other inhabitants while every one shall sit in safety under his own vine and fig tree and there shall be none to make him afraid. May the father of all mercies scatter light, and not darkness, upon our paths, and make us all in our several vocations useful here, and in His own due time and way everlastingly happy.”[ii]

During the Revolutionary War, George Washington had been supported financially by a Jewish financier, Haym Salomon, whose bronze sculpture stands at the left hand of Washington at the Heald Square Monument in Chicago, Illinois. It depicts General George Washington, and the two principal financers of the American Revolution, Robert Morris and Haym Salomon. In 1925, President Calvin Coolidge eloquently recounted Haym Salomon’s contributions and personal sacrifices for the cause of liberty: “Haym Salomon, Polish Jew financier of the Revolution. Born in Poland, he was made prisoner by the British forces in New York, and when he escaped set up in business in Philadelphia. He negotiated for Robert Morris all the loans raised in France and Holland, pledged his personal faith and fortune for enormous amounts, and personally advanced large sums to such men as James Madison, Thomas Jefferson, and many other patriot leaders who testified that without his aid they could not have carried on in the cause.”[iii] In 1975, a U.S. ten-cent postage stamp honored Haym Solomon, with printing on the back: “Financial hero-businessman and broker Haym Solomon was responsible for raising most of the money needed to finance the American Revolution and later saved the new nation from collapse.”

Twelve amendments to the Constitution had been proposed in Congress. The third amendment addressed the issue of freedom of religion and of the press. Congress passed and sent all twelve amendments to the states for ratification on September 25, 1789. State legislatures were required to consider the amendments one by one and ratify them individually. Over a period of months, the state legislatures sent the amendments back to Congress, ratifying some and disapproving others. On December 15, 1791, Virginia approved ten of the twelve proposed amendments and became the tenth and last state required to do so before the amendments became law. The first two proposed amendments had been rejected by three-quarters of all the states and could not be adopted. Therefore, the original Third Amendment, prohibiting the establishment of a state religion and ensuring freedom of the press, became the newly ratified First Amendment.

After being president of Harvard, Samuel Langdon was a delegate to New Hampshire’s ratifying convention in 1788. The Portsmouth Daily Evening Times, Jan. 1, 1891, accredited to Samuel Langdon: “By his voice and example he contributed more perhaps, than any other man to the favorable action of that body”[i] which resulted in New Hampshire becoming the ninth State to ratify the U.S. Constitution, thus putting it into effect. He told his fellow delegates: “Instead of the twelve tribes of Israel, we may substitute the thirteen states of the American union, and see this application plainly offering itself, viz. – That as God in the course of his kind providence hath given you an excellent Constitution of government, founded on the most rational, equitable, and liberal principles, by which all that liberty is secured.”[ii]

John Adams praised the Jews on many occasions in his personal correspondence. America’s second president called the Jews: “The most glorious nation that ever inhabited the earth.”[iii] He also proclaimed: “The Jews have influenced the affairs of mankind more and happily than any other nation, ancient or modern.”[iv] In a letter he wrote in 1809, Adams exclaimed: “God had ordained the Jews to be the most essential instrument for civilizing nations.”[v]

Uriah P. Levy was the first Jewish Commodore in the U.S. Navy, fighting in the War of 1812 and commanding the Mediterranean squadron. He ended the practice of flogging in the Navy. A chapel at Annapolis and a WWII destroyer were named after him. When Thomas Jefferson’s Monticello home was decaying, Levy bought it in 1836, repaired it and opened it to the public. He also commissioned the statute of Jefferson that is on display in the U.S. Capitol rotunda.

As the fabric of America was being torn apart by the Civil War, the population of the United States was thirty-one million, including around 150,000 Jews. An estimated 7,000 Jews fought for the Union and 3,000 fought for the Confederacy, with around six hundred Jewish soldiers dying in battle. The first Jewish United States Senator who had not renounced his Jewish faith, Judah P. Benjamin, resigned when Louisiana left the Union in early 1861, and was appointed by Jefferson Davis to become Attorney General, then Secretary of War, and Secretary of State for the Confederacy. His image graced the $2 bill of the Confederate States of America.

When the Civil War erupted, the Governor of Indiana asked Lewis Wallace to recruit soldiers, and within one week, Wallace had recruited six regiments. Wallace, in turn, appointed his Jewish friend, Frederick Knefler, as his principal assistant. After being assigned command of the 11th Indiana Infantry, Wallace promoted Knefler to 1st Lieutenant. Wallace’s brigade was part of Grant’s force in the capture of Fort Henry and Fort Donelson, playing a key part in preventing the Confederate forces from forcing an escape from Fort Donelson through the Union lines. Wallace's report of the battle stated that Knefler’s “prompt and efficient service in the field” and his “courage and fidelity have earned my lasting gratitude.” Frederick Knefler went on to become the highest-ranking Jewish officer in the Union Army, and Brigadier General in command of the 79th Indiana Infantry.

The Civil War ended April 9, 1865, when Confederate General Robert E. Lee signed the terms of surrender offered to him by Union General Ulysses S. Grant in the parlor of a home next to the Appomattox County Courthouse in Virginia. But the wounds ran deep – Atlanta was left a burned-out ruin; the naval yard in Norfolk, Virginia lay in ruins; Charleston, South Carolina was destroyed; infrastructure and machinery were left unusable and for years afterward, the grim recovery and burial of the dead kept America from swift recovery.

Which brings me back to Lewis Wallace, and his relationship with Frederick Knefler, Wallace’s Jewish friend, and principal assistant during the Civil War. By his own admission, Wallace had always been indifferent to religion, even though his mother had often read the bible to him as he was growing up in Indiana, where his father served as governor. Wallace wrote in his preface of his book, The First Christmas:

I heard the story of the Wise Men when I was a small boy. My mother read it to me; and of all the tales of the Bible and the New Testament none took such a lasting hold on my imagination, none so filled me with wonder. Who were they? Whence did they come? Were they all from the same country? Did they come singly or together? Above all, what led them to Jerusalem, asking of all they met the strange question, “Where is he that is born King of the Jews? For we have seen his star in the east, and are come to worship him.” Finally, I concluded to write of them. By carrying the story on to the birth of Christ in the cave by Bethlehem, it was possible, I thought to compose a brochure that might be acceptable to the Harper Brothers. When the writing was done, I laid it away in a drawer of my desk, waiting for courage to send it forward: and there it still might be lying had it not been for a fortuitous circumstance.[vi]

Wallace went on to explain that in 1876, he boarded a train bound for Indianapolis to attend a Republican Convention. “Moving slowly down the aisle of the car, talking with some friends, I passed the stateroom. There was a knock on the door from the inside, and someone called my name.

Upon answer, the door opened, and I saw Colonel Robert G. Ingersoll. ‘Was it you who called me Colonel?’ ‘Yes,’ he said. ‘Come in, I feel like talking.’ I leaned against the cheek of the door, and said, ‘Well, if you let me dictate the subject, I will come in.’ ‘Certainly, that's exactly what I want.’”[vii] Robert Green "Bob" Ingersoll was an American lawyer, a Civil War veteran, political leader, and orator, noted for his broad range of culture and his defense of agnosticism. He was nicknamed "The Great Agnostic". For two hours, Wallace was barraged with Ingersoll’s rhetoric and reasoning and left the train at the station in Indianapolis in what he described as “a confusion of mind not unlike dazement”[viii] and walked to his brother’s home.

To explain this, it is necessary now to confess that my attitude with respect to religion had been one of absolute indifference. I had heard it argued times innumerable, always without interest. So, too I had read the sermons of great preachers---Bossuet, Chalmers, Robert Hall, and Henry Ward Beecher------but always for the surpassing charm of their rhetoric. But--how strange! To lift me out of my indifference, one would think only strong affirmations of things regarded holiest would do. Yet here was I now moved as never before, and by what? The most outright denials of all human knowledge of God, Christ, Heaven, and the Hereafter which figures so in the hope and faith of the believing everywhere. Was the Colonel right? What had I on which to answer yes or no? He had made me ashamed of my ignorance: and then---here is the unexpected of the affair--as I walked on in the cool darkness, I was aroused for the first time in my life to the importance of religion. To write all my reflections would require many pages. I pass them to say simply that I resolved to study the subject. And while casting round how to set about the study to the best advantage, I thought of the manuscript in my desk. Its closing scene was the child Christ in the cave by Bethlehem: why not go on with the story down to the crucifixion? That would make a book and compel me to study everything of pertinency; after which, possibly, I would be possessed of opinions of real value. It only remains to say that I did as resolved, with results---first, the book, and second, a conviction amounting to absolute belief in God and the Divinity of Christ.[ix]

Wallace wrote most of his masterpiece underneath a beech tree in Crawfordsville, Indiana. He completed the final chapters of the novel while he was serving as Governor of the New Mexico Territory. Ben-Hur: A Tale of the Christ by General Lew Wallace was published by Harper & Brothers on November 12, 1880, and considered "the most influential Christian book of the nineteenth century”. It became a best-selling American novel, surpassing Harriet Beecher Stowe's Uncle Tom's Cabin (1852) in sales. It contributed to the healing of a nation still reeling from the ravages of the Civil War.

After Wallace's novel was published, there was widespread demand for it to be adapted for the stage, but Wallace resisted for nearly twenty years, arguing that no one could accurately portray Christ on stage or recreate a realistic chariot race. In 1899, following three months of negotiations, Wallace entered into agreement with theatrical producers Marc Klaw and A. L. Erlanger to adapt his novel into a stage production. Their elaborate staging and special effects created a life-sized visual presentation of Wallace's novel. So, Denny, how did they recreate the chariot race? Another great question. They used real horses and real chariots! They designed and built an elaborate mechanism using two electric tread mills that could be drawn back and forth to recreate changes in which chariot was in the lead with a moving painted backdrop called a cyclorama showing the interior of the arena providing the illusion of motion throughout the race. Ben-Hur opened at the Broadway Theater in New York City on November 29, 1899, and ran for eighteen non-consecutive years on Broadway. The play's twenty-one-year national tour included large venues in cities such as Boston, Philadelphia, Chicago, and Baltimore. International versions of the show played in London, England, and in Sydney and Melbourne, Australia. When the play finally closed in April 1920, it had been seen by more than twenty million people and earned over $10 million at the box office! The book was also adapted for motion pictures in 1907, 1925, 1959, 2003, 2016, and as an American television miniseries in 2010. The 1959 film adaptation, starring Charlton Heston, won a record eleven Academy Awards and was the top-grossing film of 1960.

In 1881, Wallace was appointed U.S. Minister to the Ottoman Empire by President James A. Garfield and served in the Middle East at that post until 1885. His visits to Jerusalem during his tenure made him a staunch Zionist who longed for the return of the Jewish people to their homeland. In honor of Lew Wallace, the State of Indiana placed his statue in Statuary Hall in the U.S. Capitol Building where it stands today.

Indeed, the fruitful bough which had been planted by a well is growing over the wall. The impact that Judaism has had on life in America is unmistakable.

After being president of Harvard, Samuel Langdon was a delegate to New Hampshire’s ratifying convention in 1788. The Portsmouth Daily Evening Times, Jan. 1, 1891, accredited to Samuel Langdon: “By his voice and example he contributed more perhaps, than any other man to the favorable action of that body”[i] which resulted in New Hampshire becoming the ninth State to ratify the U.S. Constitution, thus putting it into effect. He told his fellow delegates: “Instead of the twelve tribes of Israel, we may substitute the thirteen states of the American union, and see this application plainly offering itself, viz. – That as God in the course of his kind providence hath given you an excellent Constitution of government, founded on the most rational, equitable, and liberal principles, by which all that liberty is secured.”[ii]

John Adams praised the Jews on many occasions in his personal correspondence. America’s second president called the Jews: “The most glorious nation that ever inhabited the earth.”[iii] He also proclaimed: “The Jews have influenced the affairs of mankind more and happily than any other nation, ancient or modern.”[iv] In a letter he wrote in 1809, Adams exclaimed: “God had ordained the Jews to be the most essential instrument for civilizing nations.”[v]

Uriah P. Levy was the first Jewish Commodore in the U.S. Navy, fighting in the War of 1812 and commanding the Mediterranean squadron. He ended the practice of flogging in the Navy. A chapel at Annapolis and a WWII destroyer were named after him. When Thomas Jefferson’s Monticello home was decaying, Levy bought it in 1836, repaired it and opened it to the public. He also commissioned the statute of Jefferson that is on display in the U.S. Capitol rotunda.

As the fabric of America was being torn apart by the Civil War, the population of the United States was thirty-one million, including around 150,000 Jews. An estimated 7,000 Jews fought for the Union and 3,000 fought for the Confederacy, with around six hundred Jewish soldiers dying in battle. The first Jewish United States Senator who had not renounced his Jewish faith, Judah P. Benjamin, resigned when Louisiana left the Union in early 1861, and was appointed by Jefferson Davis to become Attorney General, then Secretary of War, and Secretary of State for the Confederacy. His image graced the $2 bill of the Confederate States of America.

When the Civil War erupted, the Governor of Indiana asked Lewis Wallace to recruit soldiers, and within one week, Wallace had recruited six regiments. Wallace, in turn, appointed his Jewish friend, Frederick Knefler, as his principal assistant. After being assigned command of the 11th Indiana Infantry, Wallace promoted Knefler to 1st Lieutenant. Wallace’s brigade was part of Grant’s force in the capture of Fort Henry and Fort Donelson, playing a key part in preventing the Confederate forces from forcing an escape from Fort Donelson through the Union lines. Wallace's report of the battle stated that Knefler’s “prompt and efficient service in the field” and his “courage and fidelity have earned my lasting gratitude.” Frederick Knefler went on to become the highest-ranking Jewish officer in the Union Army, and Brigadier General in command of the 79th Indiana Infantry.

The Civil War ended April 9, 1865, when Confederate General Robert E. Lee signed the terms of surrender offered to him by Union General Ulysses S. Grant in the parlor of a home next to the Appomattox County Courthouse in Virginia. But the wounds ran deep – Atlanta was left a burned-out ruin; the naval yard in Norfolk, Virginia lay in ruins; Charleston, South Carolina was destroyed; infrastructure and machinery were left unusable and for years afterward, the grim recovery and burial of the dead kept America from swift recovery.

Which brings me back to Lewis Wallace, and his relationship with Frederick Knefler, Wallace’s Jewish friend, and principal assistant during the Civil War. By his own admission, Wallace had always been indifferent to religion, even though his mother had often read the bible to him as he was growing up in Indiana, where his father served as governor. Wallace wrote in his preface of his book, The First Christmas:

I heard the story of the Wise Men when I was a small boy. My mother read it to me; and of all the tales of the Bible and the New Testament none took such a lasting hold on my imagination, none so filled me with wonder. Who were they? Whence did they come? Were they all from the same country? Did they come singly or together? Above all, what led them to Jerusalem, asking of all they met the strange question, “Where is he that is born King of the Jews? For we have seen his star in the east, and are come to worship him.” Finally, I concluded to write of them. By carrying the story on to the birth of Christ in the cave by Bethlehem, it was possible, I thought to compose a brochure that might be acceptable to the Harper Brothers. When the writing was done, I laid it away in a drawer of my desk, waiting for courage to send it forward: and there it still might be lying had it not been for a fortuitous circumstance.[vi]

Wallace went on to explain that in 1876, he boarded a train bound for Indianapolis to attend a Republican Convention. “Moving slowly down the aisle of the car, talking with some friends, I passed the stateroom. There was a knock on the door from the inside, and someone called my name.

Upon answer, the door opened, and I saw Colonel Robert G. Ingersoll. ‘Was it you who called me Colonel?’ ‘Yes,’ he said. ‘Come in, I feel like talking.’ I leaned against the cheek of the door, and said, ‘Well, if you let me dictate the subject, I will come in.’ ‘Certainly, that's exactly what I want.’”[vii] Robert Green "Bob" Ingersoll was an American lawyer, a Civil War veteran, political leader, and orator, noted for his broad range of culture and his defense of agnosticism. He was nicknamed "The Great Agnostic". For two hours, Wallace was barraged with Ingersoll’s rhetoric and reasoning and left the train at the station in Indianapolis in what he described as “a confusion of mind not unlike dazement”[viii] and walked to his brother’s home.

To explain this, it is necessary now to confess that my attitude with respect to religion had been one of absolute indifference. I had heard it argued times innumerable, always without interest. So, too I had read the sermons of great preachers---Bossuet, Chalmers, Robert Hall, and Henry Ward Beecher------but always for the surpassing charm of their rhetoric. But--how strange! To lift me out of my indifference, one would think only strong affirmations of things regarded holiest would do. Yet here was I now moved as never before, and by what? The most outright denials of all human knowledge of God, Christ, Heaven, and the Hereafter which figures so in the hope and faith of the believing everywhere. Was the Colonel right? What had I on which to answer yes or no? He had made me ashamed of my ignorance: and then---here is the unexpected of the affair--as I walked on in the cool darkness, I was aroused for the first time in my life to the importance of religion. To write all my reflections would require many pages. I pass them to say simply that I resolved to study the subject. And while casting round how to set about the study to the best advantage, I thought of the manuscript in my desk. Its closing scene was the child Christ in the cave by Bethlehem: why not go on with the story down to the crucifixion? That would make a book and compel me to study everything of pertinency; after which, possibly, I would be possessed of opinions of real value. It only remains to say that I did as resolved, with results---first, the book, and second, a conviction amounting to absolute belief in God and the Divinity of Christ.[ix]

Wallace wrote most of his masterpiece underneath a beech tree in Crawfordsville, Indiana. He completed the final chapters of the novel while he was serving as Governor of the New Mexico Territory. Ben-Hur: A Tale of the Christ by General Lew Wallace was published by Harper & Brothers on November 12, 1880, and considered "the most influential Christian book of the nineteenth century”. It became a best-selling American novel, surpassing Harriet Beecher Stowe's Uncle Tom's Cabin (1852) in sales. It contributed to the healing of a nation still reeling from the ravages of the Civil War.

After Wallace's novel was published, there was widespread demand for it to be adapted for the stage, but Wallace resisted for nearly twenty years, arguing that no one could accurately portray Christ on stage or recreate a realistic chariot race. In 1899, following three months of negotiations, Wallace entered into agreement with theatrical producers Marc Klaw and A. L. Erlanger to adapt his novel into a stage production. Their elaborate staging and special effects created a life-sized visual presentation of Wallace's novel. So, Denny, how did they recreate the chariot race? Another great question. They used real horses and real chariots! They designed and built an elaborate mechanism using two electric tread mills that could be drawn back and forth to recreate changes in which chariot was in the lead with a moving painted backdrop called a cyclorama showing the interior of the arena providing the illusion of motion throughout the race. Ben-Hur opened at the Broadway Theater in New York City on November 29, 1899, and ran for eighteen non-consecutive years on Broadway. The play's twenty-one-year national tour included large venues in cities such as Boston, Philadelphia, Chicago, and Baltimore. International versions of the show played in London, England, and in Sydney and Melbourne, Australia. When the play finally closed in April 1920, it had been seen by more than twenty million people and earned over $10 million at the box office! The book was also adapted for motion pictures in 1907, 1925, 1959, 2003, 2016, and as an American television miniseries in 2010. The 1959 film adaptation, starring Charlton Heston, won a record eleven Academy Awards and was the top-grossing film of 1960.

In 1881, Wallace was appointed U.S. Minister to the Ottoman Empire by President James A. Garfield and served in the Middle East at that post until 1885. His visits to Jerusalem during his tenure made him a staunch Zionist who longed for the return of the Jewish people to their homeland. In honor of Lew Wallace, the State of Indiana placed his statue in Statuary Hall in the U.S. Capitol Building where it stands today.

Indeed, the fruitful bough which had been planted by a well is growing over the wall. The impact that Judaism has had on life in America is unmistakable.